As strange as it may sound, the story of codfish is intimately connected with the history of Portugal. Behind this beautiful fish hides the story of a small country that was able to conquer the world to later become small again, rich in its fair size.

To talk about codfish in Portugal is to talk about family, dinners with friends, the Christmas night; but it also to talk about the Portuguese discoveries, our long dictatorship, the 25th of April of 1974 (the day when it was finally over). It is a journey to our collective memories, that have been forgotten and that I will try to rescue.

Finally, to talk about codfish is also to talk about Porto. Here we are all pretty crazy about cod too, and in Porto there are some lovely grocery stores specialised in codfish, that one day I will write about.

But for now, let me tell you the story of codfish in Portugal, which is something I am asked every single week 🙂

And, if you want to learn more secrets about the Portuguese food scene, don’t hesitate to join a Food tour in Porto!

Codfish in Portugal: an historical background

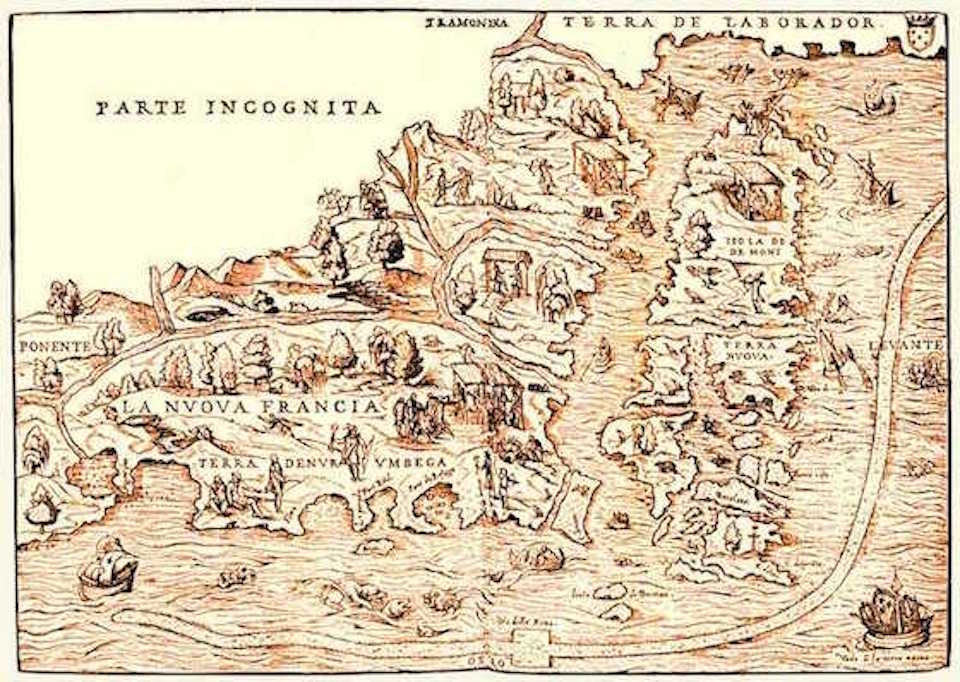

The first records of Portuguese fleets fishing cod off the coast of Newfoundland date from the sixteenth century. The cod fishery thus appears closely associated with the heyday of the Portuguese sea discoveries.

As cod was fished in such far away (and cold) waters, it was pickled in salt to withstand the long journey back home. The British Navy provided protection to the Portuguese fishing fleets in exchange for salt, an extremely valuable asset at the time, and that Portugal produced in large quantities.

Interestingly, cod fishing, which during the sixteenth century was dominated by Portuguese fleets, escaped our hands during the following centuries, virtually until the early twentieth century.

Due to the adverse action of the British and Spanish fleets, and the indifference of the Portuguese crown (much more interested in the East), cod stopped being caught by Portuguese fleets, and started being supplied by Britain.

The beginning of the military dictatorship, in 1926, radically changed the situation. As meat was very expensive and with severe supply problems of fresh fish to the countryside, cod was a central ingredient of the diet of the working classes.

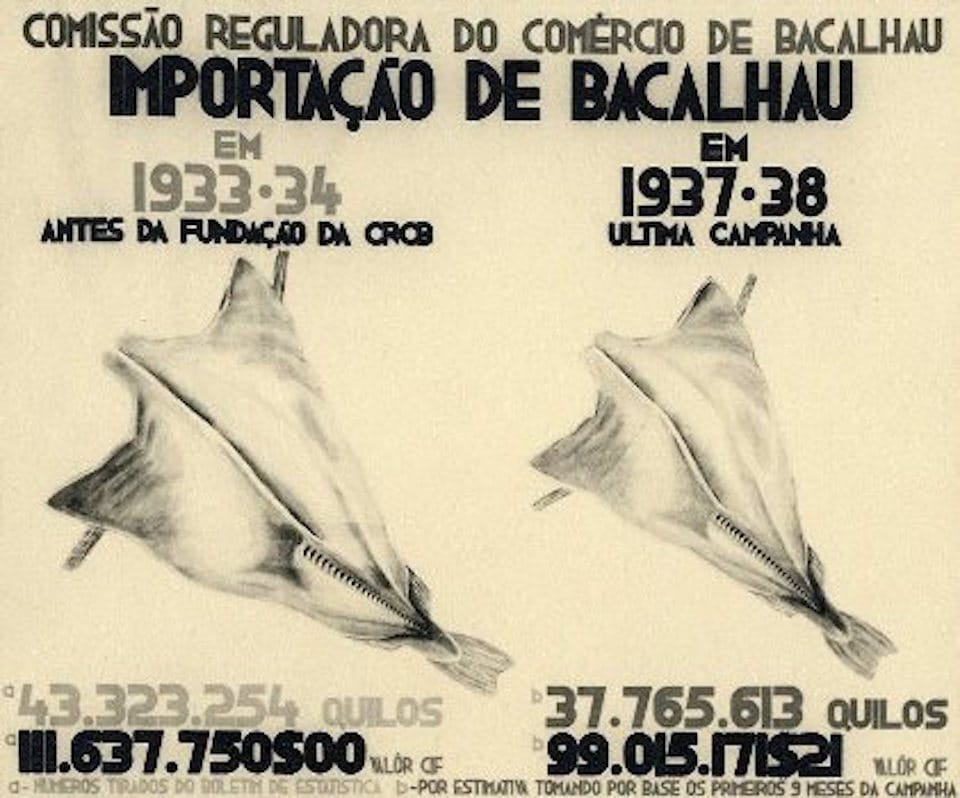

It became a key issue for the regime, which initiated the so called “Cod Campaign”, aimed at boosting domestic production capacity, decreasing dependence on imports.

The entire operation was controlled by the Portuguese Government, which set prices, guaranteed a disciplined workforce (through coercive recruitment), provided cheap financing to ships owners and conditioned the imports of cod.

In 1942 it implemented a refurbishment program of the cod fishing fleet, which went from 34 ships (1934) to 77 (1958). In just a few decades, more than 80% of cod consumption in Portugal was provided by domestic production.

The Portuguese sailors of the codfish fleet

We shall not be lured by the glorious aura of these men, though. As soon as they arrived to Newfoundland, they would start fishing in small boats called Dóris, which carried only one man.

Sometimes apart of the main ship more than two miles, each solitary fisherman would fish for up to 8 / 10h, facing horrific atmospheric conditions.

The return of all Dóris’ to the main ship marked the beginning of the second part of the job, also very time consuming: it was necessary to climb all caught fish and immediately salt it on the ship’s hold.

It was a life of sacrifice, subjected to the whims of the ocean, a low salary and the distance to the motherland.

The end of the Portuguese dictatorship and its impact on the codfish industry

During the 60’s, with the liberalization of both imports and prices, the Portuguese cod fishery started to decline. In 1974, when the dictatorship was finally over, brought an end to an extremely violent labor regime that fishermen were subjected to, and the establishment of exclusive economic zones, was the final blow of this industry.

With limited fishing zones, without access to experienced fishermen at low prices and competing with international markets, Portuguese cod fishery was soon over.

Prices rose to a point that today no one buys an entire cod, as my grandparents used to do. But it is comforting to know that cod kept a very special place on our tables, free of depreciative social connotations, applauded by all the tourists who visit us.

Save this article for later: